The exterior of the Loew’s Kings in the 1960s.

Several people served as managers of the Kings since it opened in 1929. The first was Edward Douglas who managed the theater until 1943. Clyde Fuller, who managed from 1943 to 1957, followed Douglas before moving to the Loew’s State in Manhattan. Daniel Cohen, who worked at the Kings from 1957 to October 1961 and left to take a job in the publicity department of the Loew’s corporate office, replaced Fuller. Joe Beck was transferred from the Loew’s Gates Theatre to replace Cohen. During his tenure as manager, Beck arranged for a local ice cream parlor to provide coffee and doughnuts to patrons waiting in line to see Breakfast at Tiffany’s on opening day. Beck managed the Kings for a little over a year before being transferred to the Loew’s Tower East in Manhattan’s Upper East Side in March 1962.

Dorothy Solomon Panzica sitting on the organ console at the Kings Theatre.

However, none of these managers were quite as unique as Dorothy (Solomon) Panzica. Born near Boston and raised in Brooklyn, Panzica began her theater career as an usherette at the Loew’s 46th Street Theatre in Brooklyn. By 1942, she had been promoted to manager. She had managed six other Loew’s theaters (the Kameo, 46th Street, Brevoort, Palace, Commodore, and Oriental) before being transferred to the Kings in March of 1962. When she found out she was going to the Kings, Panzica reached out to Nick’s Moving Company, one of the tenants at the Loew’s Oriental. She wanted to make the move a larger than life event and she convinced Nick to provide a moving van for an impromptu parade from the Oriental to the Kings. Panzica had a banner made that read “The Fun is moving to the Loew’s Kings” and had it hung from the moving van. She filled the van with empty trunks that were decorated to look like movie tickets and concession treats, and began the four-mile drive from the Oriental to the Kings. Local school bands marched at both theaters, each playing a synchronized salute to American composer George M. Cohan.

Panzica had a rather unorthodox way of promoting movies, and that lead to her becoming known as the “Lady Showman of Flatbush Avenue.” For example, if she didn’t like the film that was playing she’d put, “One of the WORST movies we’ve shown” on the marquee, and that caused people to show up to see just how bad the film could be. Another time, people were not coming to see a movie that was playing so she instructed the ticket taker to start selling tickets and making change very slowly. Before long, a line started to form and more people would join it thinking that the movie was one worth waiting for. Panzica also rented out the theater for other functions, such as school graduations and group meetings. She brought in so much extra money through the rentals that she often won contests held by Loew’s.

Panzica heard that Governor Nelson Rockefeller was going to make an appearance at the opening of the lower level of the Verrazano Bridge on June 28, 1969 so she sent four ushers to the bridge with signs promoting Mackenna’s Gold, which was scheduled to open at the Kings the following month.

Loew’s opened a modern twin theater in the Georgetown neighborhood of Brooklyn in 1968. The Georgetown Twin, as it was called, had one thing the Kings lacked – a large parking lot. Patrons flocked to the new theater, and eventually the Kings started showing films 20 minutes after they started at the Georgetown so they could get the overflow from the sold out showings.

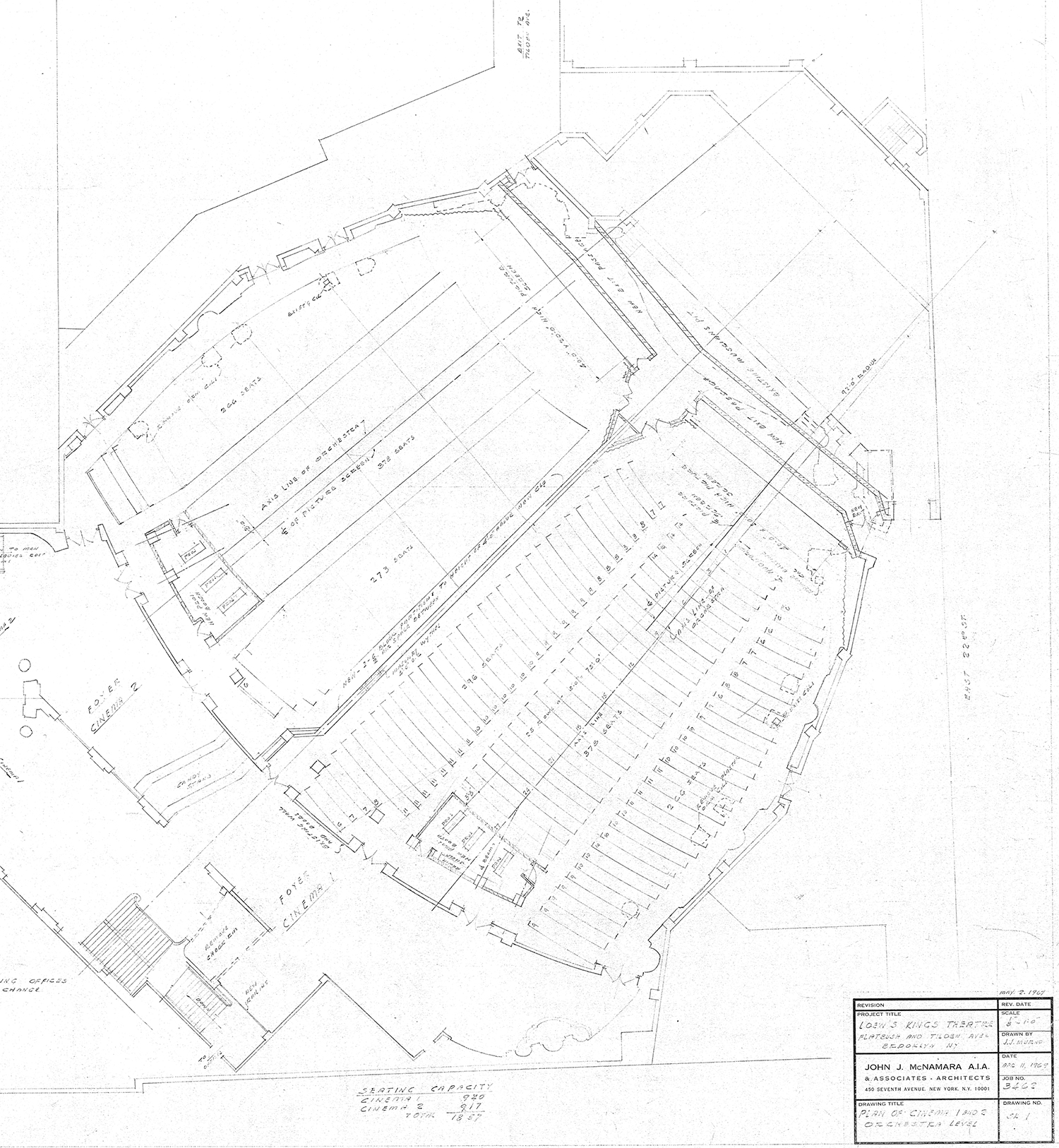

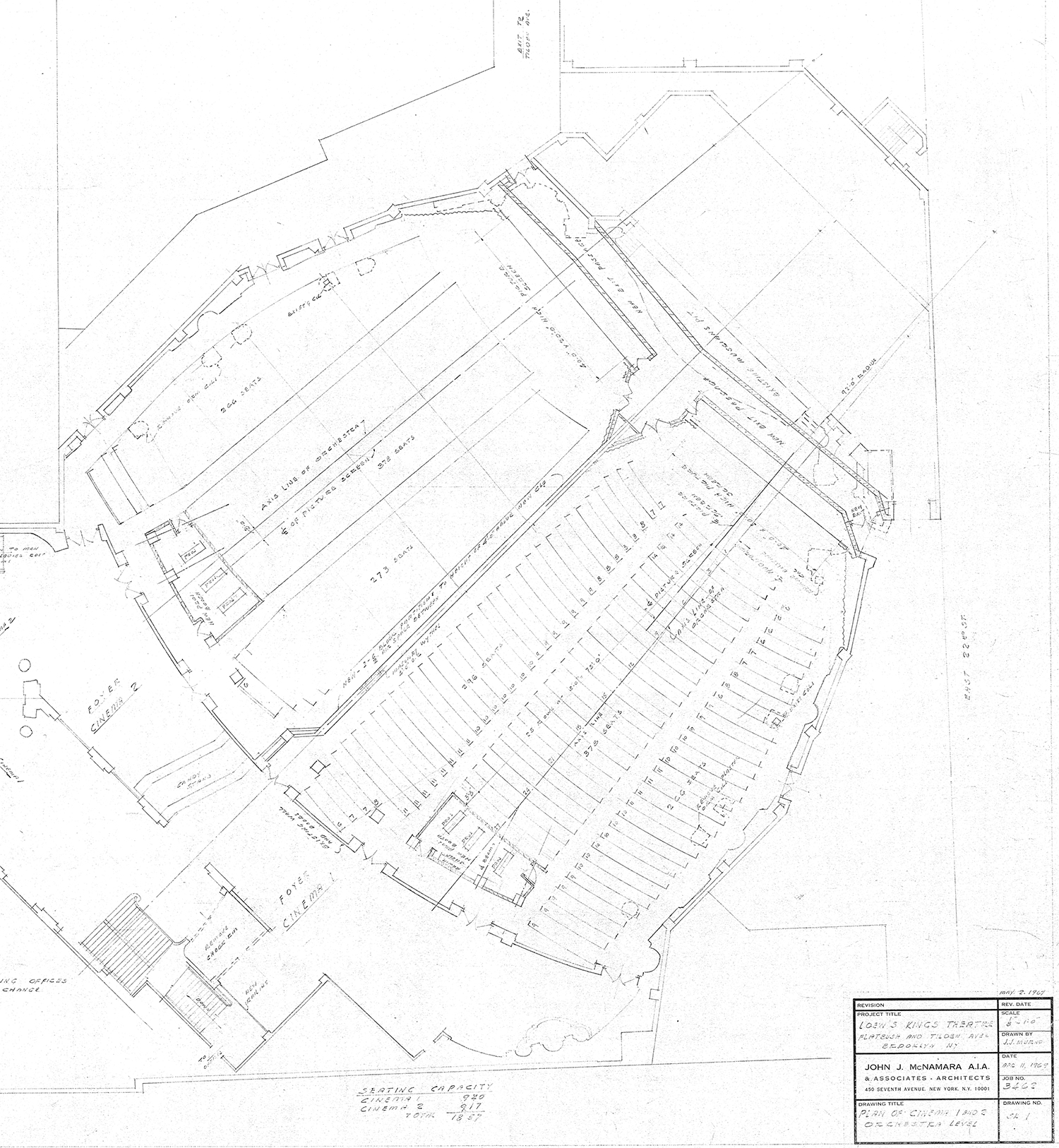

Blueprints for the proposed division of the Kings Theatre auditorium by the John J. McNamara Architectural firm. McNamara was an associate of famed theater architect Thomas W. Lamb.

In early 1969, Loew’s hired John J. McNamara, an associate of well-known theater architect Thomas W. Lamb, to convert the Kings from a single screen theater to a triplex. The plans called for the orchestra level to be divided into two screens with a third screen in the balcony. The balcony floor would have extended to the proscenium, and much of the ornamental plaster, including the columns would have been removed. Since the balcony of the theater is very short, the cost of extending it and dividing the orchestra would have been excessive. Dorothy Panzica paid a visit to Loew’s Corporate Headquarters in Midtown Manhattan as soon as she heard about these plans and convinced them to preserve the theater as a single screen.

The Kings 40th anniversary cake was donated by Ebinger’s, a Brooklyn bakery known for the “Brooklyn Blackout” Cake

1969 was also the 40th anniversary year of the Kings, and Dorothy Panzica made sure there was a huge celebration. Together with the Flatbush Merchants Association, the theater celebrated the occasion with a month of contests and prizes culminating in a gala event at the theater on October 3, 1969. The Purple Wood, a band that has since faded into obscurity, entertained crowds in front of the theater. Eventually the crowds grew so large that police had to cordon them off from the arriving guests. Ebinger’s, a local Brooklyn bakery, baked a special cake that read “Congratulations Loew’s Kings 40th Anniversary – Donated by Ebinger’s” just for the occasion. Among the people attending the event were: Brooklyn Borough President Abe Stark, Jack Rosenberg (president of the Flatbush Merchants Association), Bernard Diamond (VP of Loews Theatres), Harold Graff (Loews Division Manager), and Daniel Cohen (Loews Eastern General Manager and former manager of the Kings).

Panzica’s promotion for The Way We Were was inspired by an article in Flatbush Life titled “Filthy Flatbush Avenue.”

Flatbush experienced a shift in demographics in the late 1960s and early 1970s. Many of the Italian, Irish, and Jewish families that once made up the neighborhood moved to the suburbs, and businesses began to follow. In early November 1973, Panzica picked up the theater’s copy of Flatbush Life and saw the front-page article titled “Filthy Flatbush Avenue.” She was outraged and immediately set up a meeting with a number of local merchants, who, like Panzica, were angry at the article because it would drive customers away. The group brainstormed a number of ideas before deciding that they should organize a neighborhood cleanup. Panzica, ever the show-woman, used the cleanup to promote an upcoming film – The Way We Were starring Barbra Streisand and Robert Redford. She had signs made that said, “Flatbush is beautiful. We are polishing up ‘The Way We Are’ for ‘The Way We Were.’ See Streisand and Redford Together at the Loew’s Kings starting Wed Nov. 14th.” Ushers and volunteers carried those signs as they swept and picked up trash along Flatbush Avenue. Panzica was awarded first prize in the Columbia Pictures The Way We Were showmanship contest for her efforts in promoting the film.

Employees of the Kings Theatre cleaning up Flatbush Avenue.

In January 1974, the “Mighty Morton” organ was played for the last time at the Kings by Lee Erwin for an audience of around 200. The 3,000-pipe organ had been largely unused, only being played during graduation ceremonies and special events. The Loews Corporation donated the organ to New York University, as the Tisch Brothers, who owned a controlling interest in Loews, were alumni of the school. Panzica said, “I’ll miss the beautiful old thing. I’m sad, but in a happy sort of way.”

Panzica shutting the power to the marquee and upright sign on her last day at the Kings Theatre in 1975.

Panzica announced her retirement in September 1975. She was so beloved that the week of her retirement the Loew Down, Loew’s weekly newsletter, was entirely devoted to her career. Martin Brunner, who previously managed the Loew’s Gates in Brooklyn, replaced Panzica as manager. Brunner was used to programming for a different demographic and began bringing in a lot of kung fu and “B” films to show at the Kings. According to Paul Lepelletier, Brunner did not promote the films like Panzica and also failed to bring in outside groups to rent out the theater. Attendance began to decline and, at the same time, the cost of keeping the theater open was going up. Rumors began to circulate that Loews was going to sell the Kings.

Dorothy Solomon Panzica looking at photographs of the restored Kings Theatre in her nursing home shortly before the theater reopened.

Material from for this post was taken from the first three chapters of my book, Kings Theatre; The Rise, Fall and Rebirth of Brooklyn’s Wonder Theater. If you’d like to buy a copy they are available on Amazon, and on my website.

Historic photographs and blueprints are from the archival collections of the Theatre Historical Society of America, and the Goodman family.