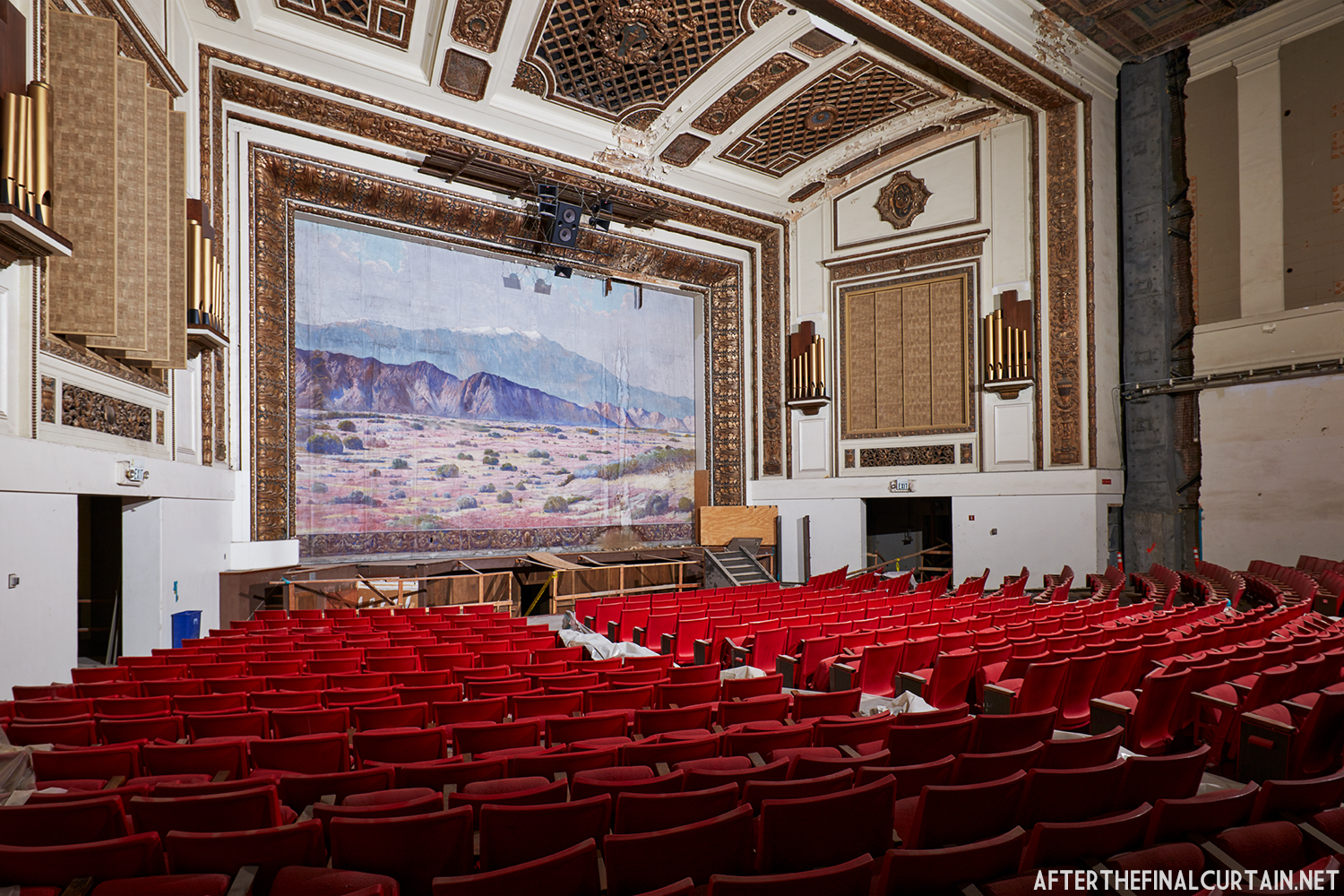

View of the auditorium from the orchestra level

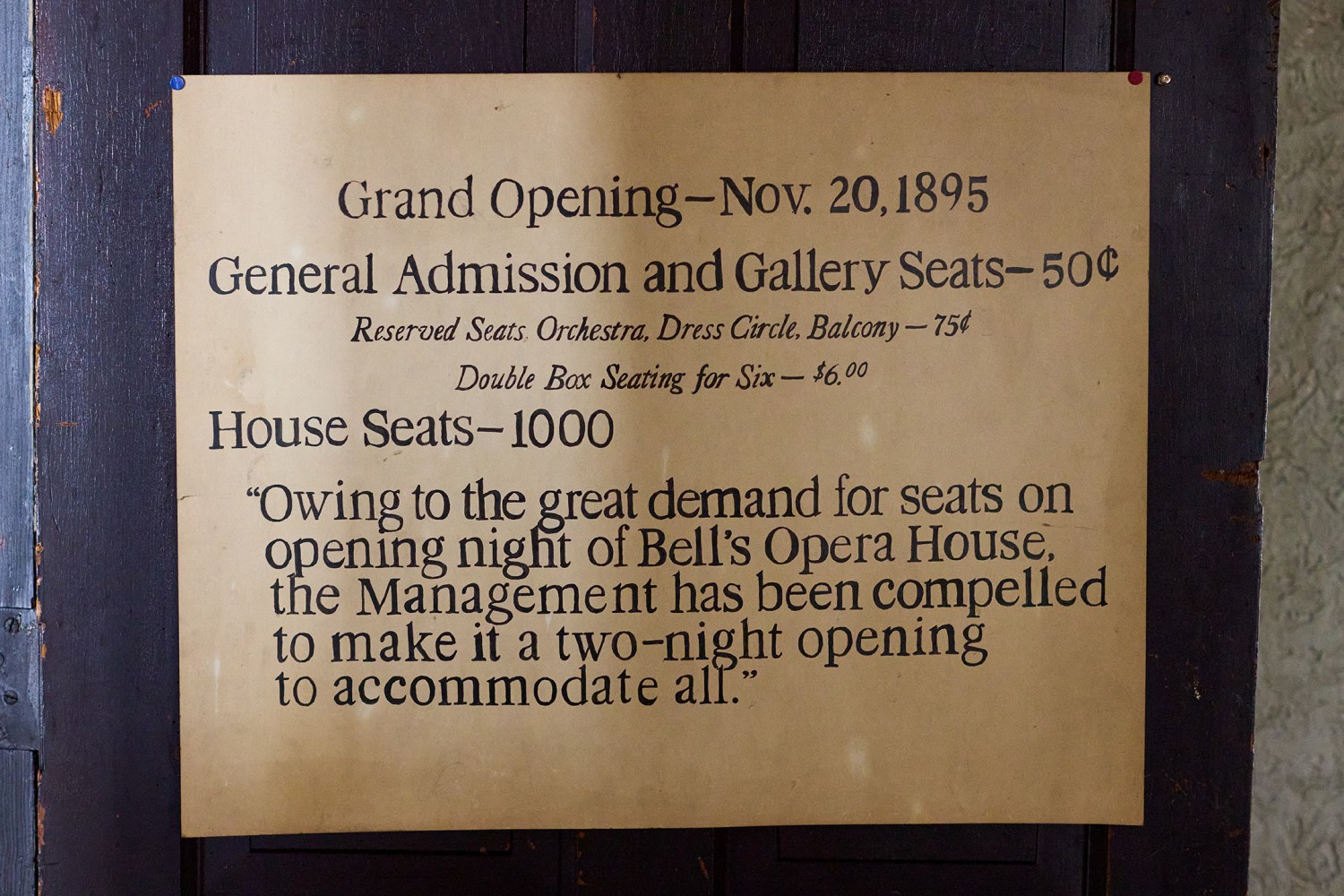

Bell’s Opera House officially opened on November 20, 1895, after just seven months of construction in Hillsboro, Ohio. It was built on South High Street, on a site once known as Rats’ Row, with a nearly 1,000-seat second-floor auditorium. The total construction cost came in at $40,000—about $1.5 million in today’s dollars—funded primarily by local manufacturer and philanthropist C.S. Bell.

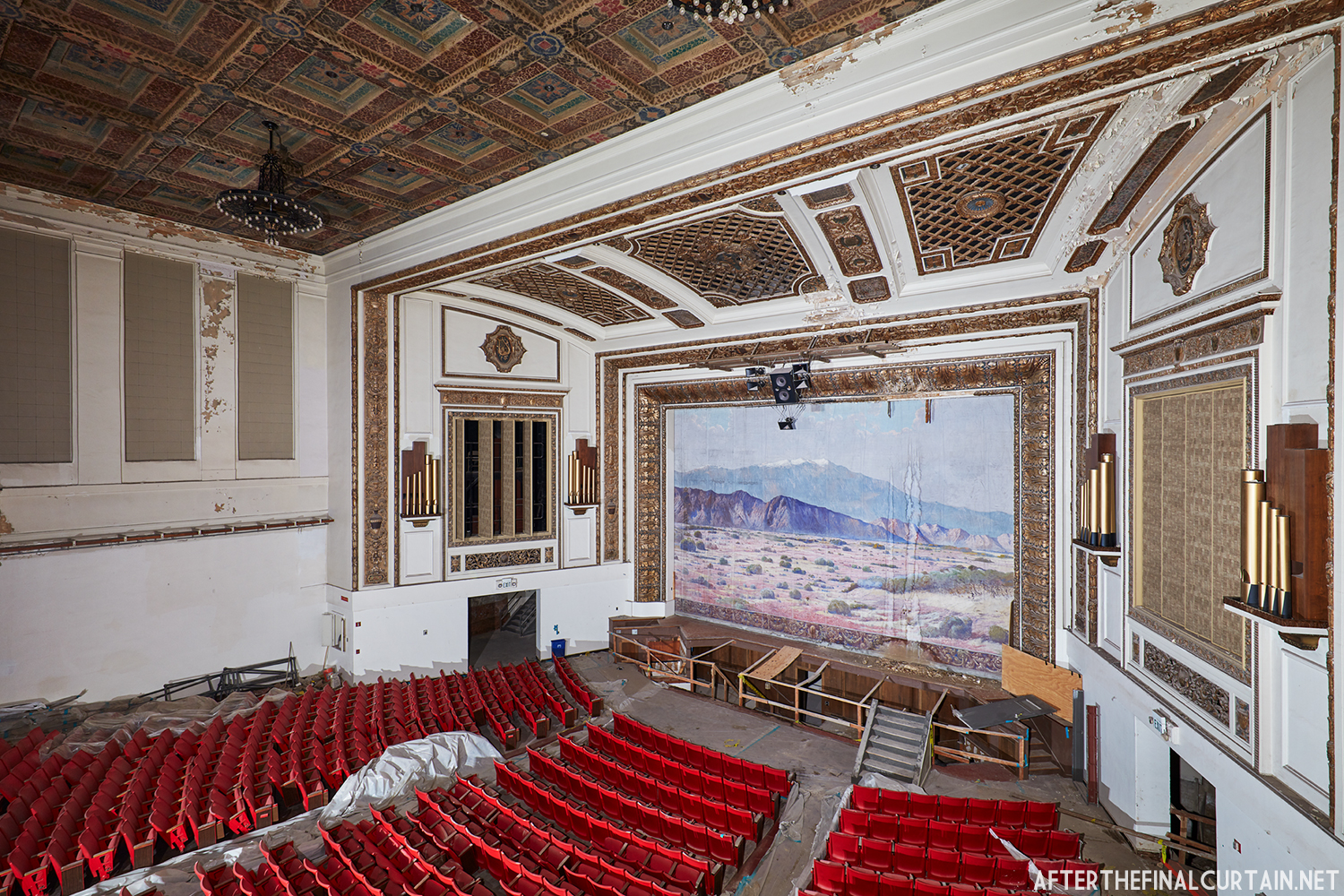

View of the auditorium from the stage.

Bell agreed to cover most of the cost if Hillsboro residents could raise $3,000 toward the project. Once the money was secured, work began in April 1895. The opening celebration stretched across two nights due to ticket demand, with performances of Friends by Edwin Milton Royle and a four-act romantic drama titled Mexico.

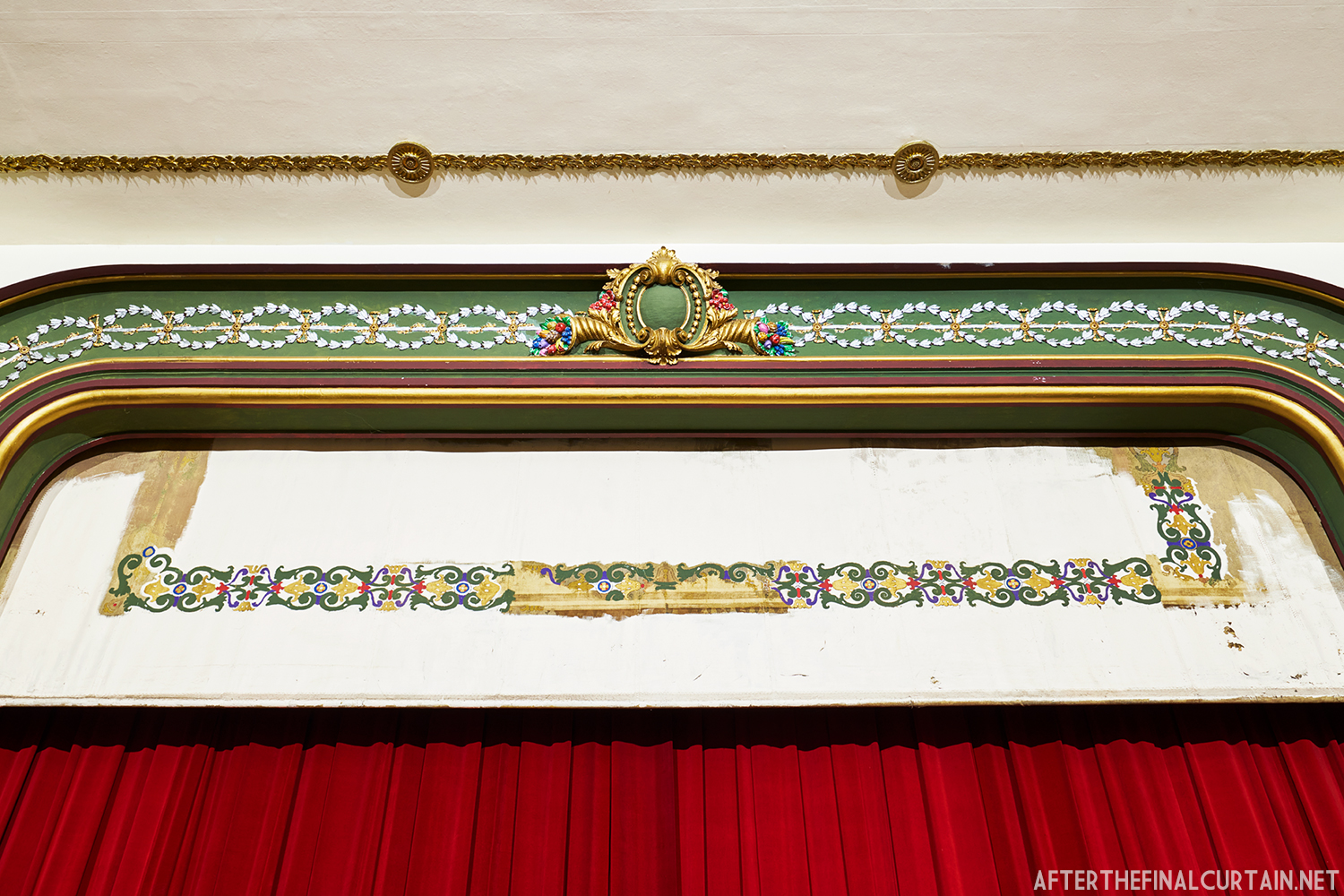

Unfortunately, the fire curtain was stuck.

The Opera House began showing silent films in 1903, starting with The Great Train Robbery. In the 1920s, it was converted into a sound-equipped movie house and rebranded as Bell’s Theatre. Ownership passed to Chakeres Theatres in 1939, but the venue closed just a few years later in 1942.

While there were brief revivals—including a return to live theater in 1957 for Ohio’s sesquicentennial—the building mostly sat dark for the second half of the 20th century. Its doors opened occasionally for festivals and local events through the 1990s.

Many of the theater’s original metal-frame seats were removed and sold for scrap during World War II. Others were reused in local schools or theaters. By the 2000s, Bell’s Opera House was largely forgotten, its interior aging but still structurally sound.

View of the auditorium from the projection booth.

In 2006, comedian and former mayor Drew Hastings purchased the building and began light restoration work in 2010–11. While stabilized, the building still needs significant investment to return it to public use. Hastings has said he hopes to sell it to a nonprofit that can complete the work and bring it back to life.

The projection booth was mostly cleaned out.

Kirsten Falke-Boyd, a classically trained singer and the great-granddaughter-in-law of C.S. Bell, visited the Opera House in 2023. Falke-Boyd was part of Bobby McFerrin’s Voicestra and has performed across the world. She described the space as both fragile and hauntingly beautiful, with its pressed tin ceiling, private box seats, and faded wallpaper still intact For her, it was more than a building—it was family history.

Some of the seats remain in the lobby.